Recently I’ve become very interested in Operational Technology (OT) security, more specifically Industrial Control System (ICS) security. Systems such as these require a unique perspective when it comes to securing them, particularly because they are so different to the standard kind of systems we secure in IT.

The scope of this post is to define a basic understanding of what an ICS is, and what the security architecture for one of these systems might look like. Please note that I am still learning myself, so my apologies for any mistakes and feedback is more than welcome.

What is an ICS?

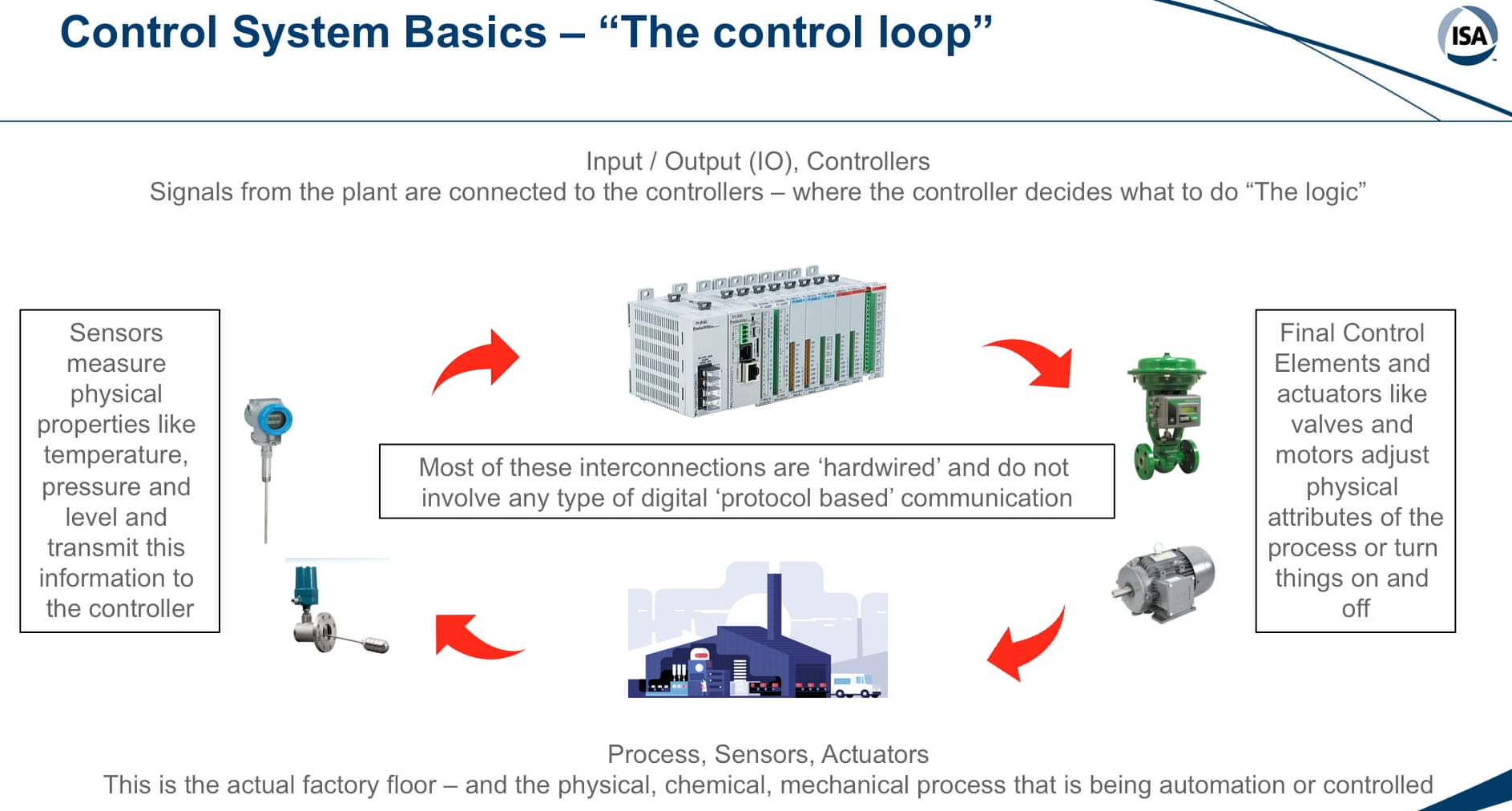

Rather than butchering the definition, here’s how Marty Edwards, ICS/OT Security SME, describes what ICS are: “All Industrial Control Systems are designed for one primary purpose - and that is to automate a physical process. They accomplish this through sensors to measure physical properties and actuators to manipulate those properties.”

Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs)

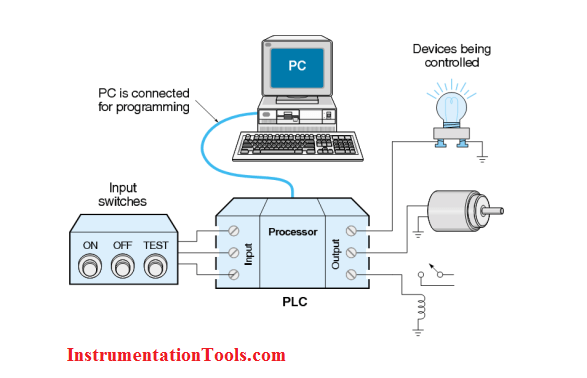

One example of ICS are Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) - PLCs are ruggedized industrial computers that act as a middleman. They modulate outputs such as actuators depending on how they are programmed and what input they receive (generally input from sensors). These are used more in discrete manufacturing with more digital inputs and on/off type control such as automobile manufacturing.

ICS Security Architecture Principles (The Purdue Model)

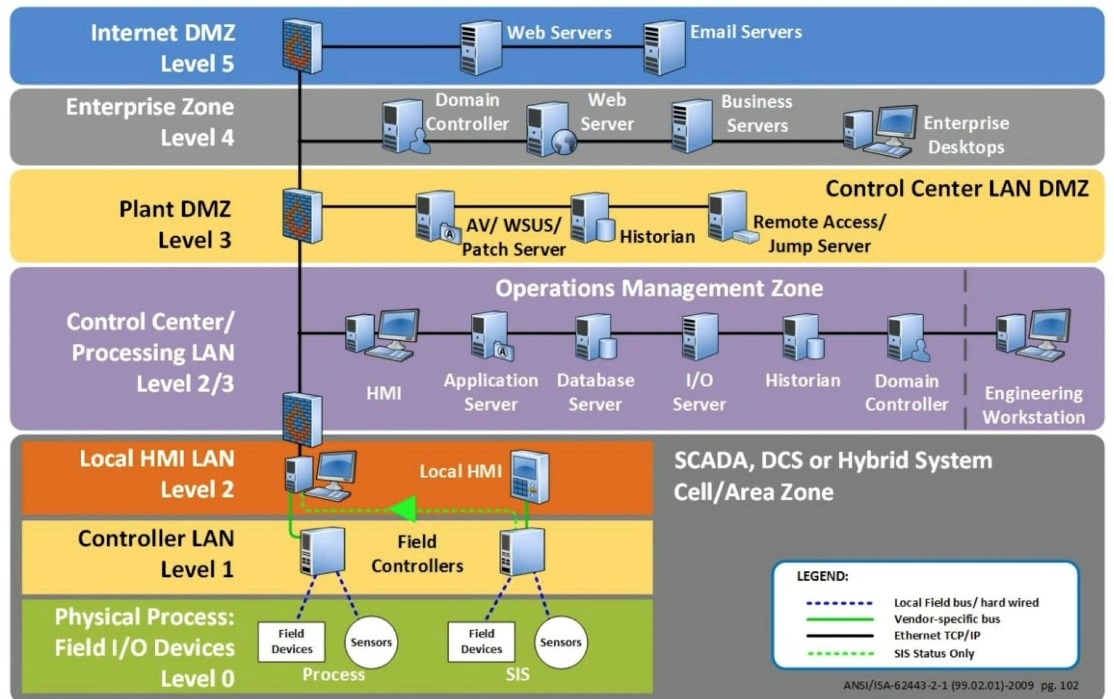

The above image is an example of the Purdue Model. This is a widely accepted standard in ICS architecture that defines the different layers of seperation and how they should interact. ICS security architecture is all about creating a strong perimeter and then aggressively limiting what is allowed through that perimeter. Least privilege and defence in depth are the key phrases here.

Least privilege in terms of minimizing what and who is allowed to pass through the enterprise/internet DMZ’s and firewalls, and into your control centre or physical processing network. Defence in depth in terms of having multiple layers of protection and network segmentation.

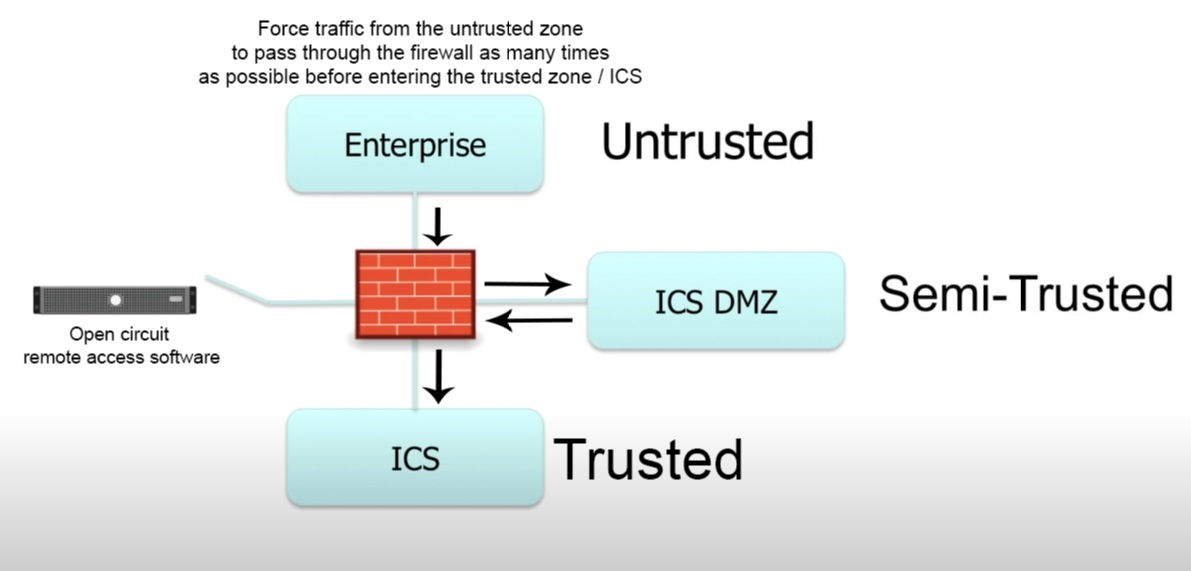

The foundation of this is having multiple firewalls and often multiple DMZ’s that a connection, or an attacker, has to pass through in order to reach the most sensitive part of your network (the physical process or controller network). This forces an attacker to have to compromise multiple networks and firewalls before reaching your trusted zone, rather than them being able to access the trusted zone right from your enterprise network.

Ideally, you would also have a separate ICS AD domain, dedicated switches and/or a dedicated virtual environment just for your ICS network. Not having these means more risk is introduced into the system. However, it is not our job to determine how much risk is acceptable.

Remote Access

A common point of failure is the remote access or jumpbox software. These remote access servers are often placed in the DMZ between an enterprise and control network and are used in emergencies to complete maintenance or access the plant control when not otherwise possible. The successful attack on the Ukrainian power grid was performed via spearfished remote access credentials.

Remote access capabilities should always be an open circuit when not in use, i.e. it’s default state should be off. And when remote access is needed it should automatically turn off after n seconds in order to avoid the human error of leaving it on indefinitely and increasing your attack surface exponentially.

I hope this post has given you a bit of an introduction to ICS security architecture. I am still learning more myself so will be publishing more posts about this topic and ICS security in general in the future.